This post is part two in a series on how to diagram rules for linear games. The goal is to give you “plain English” explanations of some of the more challenging LG rules so that you can diagram them with confidence.

Here are the rules covered in this series:

Part 1

- Usain finished the race 3 spots in front of Carl.

- Usain finished the race at least 3 spots in front of Carl.

- Usain finishes before Carl, and at least one other person finishes between them.

Part 2 <— You are here.

- Turner is before Quinn or after Fernandez but not both.

- Neither Fernandez nor Quinn can be seen before Turner.

- Fernandez and Quinn cannot both be seen before Turner.

- Either Fernandez or Quinn, but not both, must be seen before Turner.

Part 3

- If Samuel is before Jacqueline, then Marco must be after Liu.

- Samuel is before Jacqueline only if Marco is after Liu.

- If Liu is before Marco, he must be immediately before Marco.

- Samuel must play immediately behind Jacqueline unless Liu plays before Marco.

Rule 2a: Turner is before Quinn or after Fernandez but not both.

In order to get the “plain English” interpretation of this rule, let’s think about what it really means. There are three things this rule is really saying:

1. Turner is before Quinn.

OR

2. Turner is after Fernandez.

BUT

3. Both of these things are not true at once.

Let’s skip over that third part for now, since that’s where things get more complicated. First, let’s think about how to diagram the first two parts:

1. Turner is before Quinn: T – Q

2. Turner is after Fernandez: F – T

The thing about “or”

Now, normally on the LSAT, the word “or” always implies “or both.” In other words, if I tell you that you get soup or salad with your meal, the LSAT would have no problem with you asking for BOTH soup AND salad. That’s not how things work in the real world a lot of the time. But LSAT isn’t the real world! For the LSAT to prevent you from getting BOTH the soup AND the salad, they’d have to say “you get soup or salad with your meal, but not both.”

The “but not both” is at play here in this rule. So let’s figure it out.

How to handle “but not both”

The trick to “but not both” rules is to know that if we have one of the things (the soup), then we can’t have the other (the salad).

So if we have Turner before Quinn, then we can’t have Turner after Fernandez. In other words, we’d have to have Turner BEFORE Fernandez (assuming no funny business like they can occur together). This means:

T – Q and T – F

which we can represent like this:

Alternatively, we could have Turner after Fernandez (the second option above). In that case, we can’t have Turner before Quinn. So he’d have to be AFTER Quinn. This means:

F – T and Q – T

which we can represent like this:

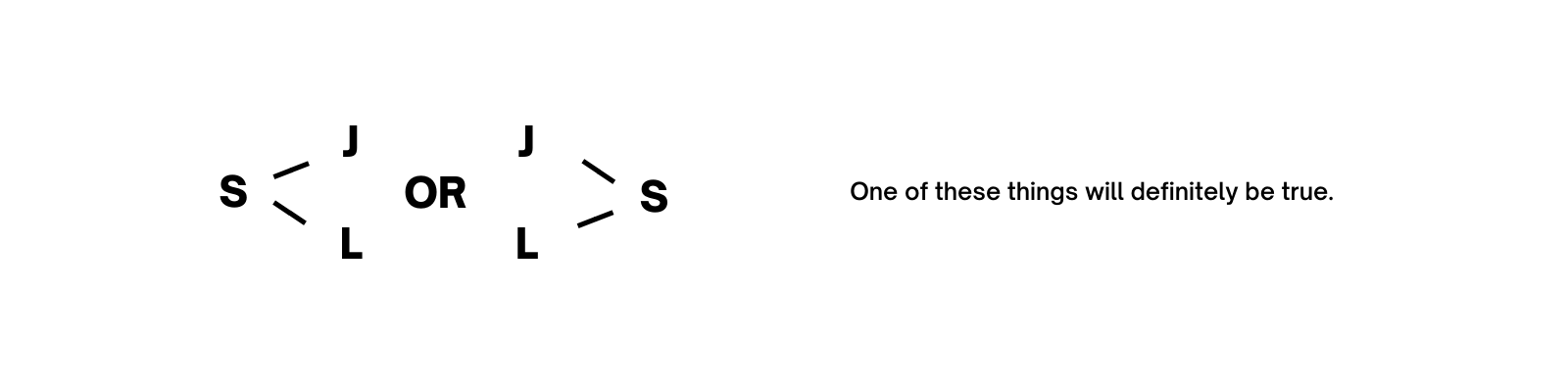

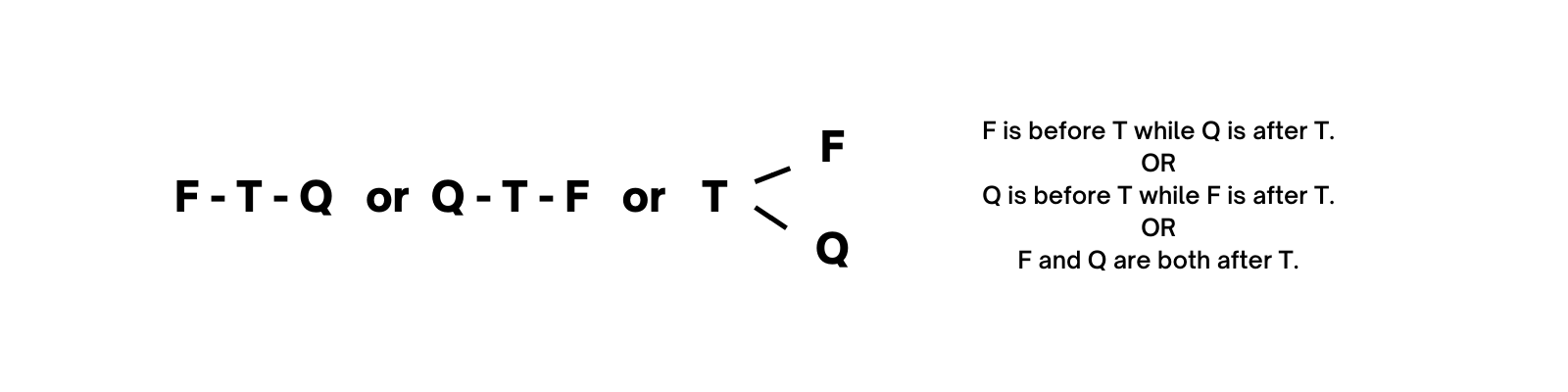

Either one of these would follow the rule, and we have to have one of these two. So on your scratch paper, you should end up with this:

The plain English

Looking back at the sketch, we should notice that Quinn and Fernandez are both on the same side of Turner. Either they’re both before him or they’re both after him. We can’t split them up and have Turner between them. After we’ve made the sketch, it’ll help us internalize the rule and apply it in the game if we get this “plain English” interpretation of the rule as well.

Rule 2b: Neither Fernandez nor Quinn can be seen before Turner.

This is another rule with multiple parts, so let’s break it down again. If we think about the English, what it’s really saying is:

1. Fernandez cannot be seen before Turner.

AND

2. Quinn cannot be seen before Turner.

How to handle “neither… nor”

It can be a little tricky to get your mind to interpret “neither.. nor” as an “and” situation, but think about this sentence: “Neither my 8-month old son nor my 3-year-old niece can drive.” We should be able to describe the same situation in two sentences: “My 8-month-old cannot drive. My 3-year-old niece cannot drive.” Notice how when we separate it into two sentences, the “can drive” in the original sentence becomes a “cannot drive” in the new sentences. That’s because the original sentence conveyed the negative meaning in the words “neither… nor,” which we replaced.

Putting the two sentences together

So, we’ve taken the original sentence “Neither Fernandez nor Quinn can be seen before Turner.” and have broken it into two parts:

1. Fernandez cannot be seen before Turner.

AND

2. Quinn cannot be seen before Turner.

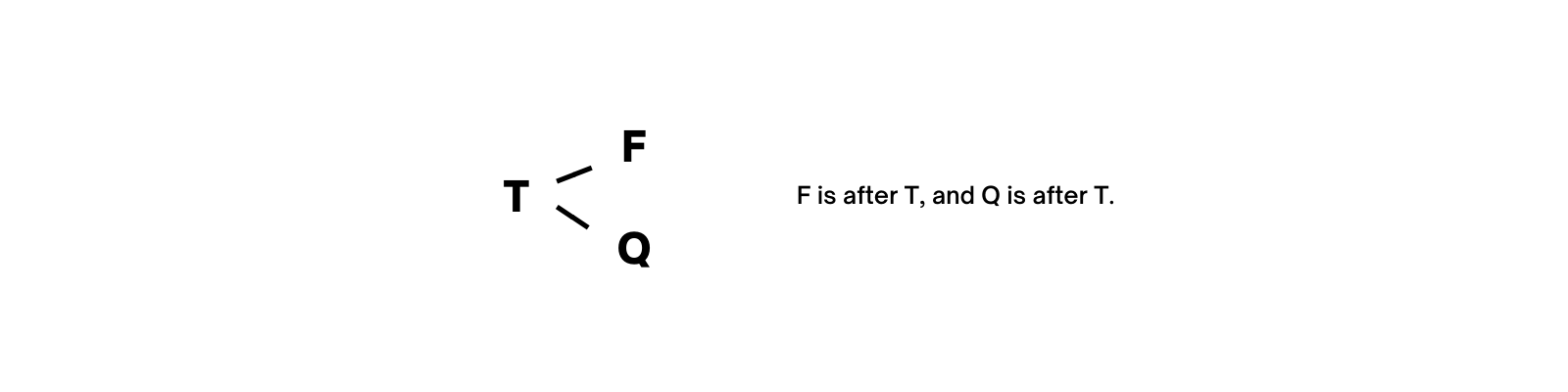

Before we diagram them, let’s think about what they mean. Assuming people can’t double-up and be seen at the same time as someone else, then “Fernandez cannot be seen before Turner” means that “Fernandez has to be seen after Turner.” Same thing for Quinn. Positively worded rules are easier to deal with than negatively worded rules, so let’s do it that way:

1. Fernandez must be seen after Turner. T – F

AND

2. Quinn must be seen after Turner. T – Q

Putting these together, we get this:

The plain English

Looking at this diagram, you should tell yourself “Make sure that F and Q are both later than T.”

Rule 2c: Fernandez and Quinn cannot both be seen before Turner.

This difference between this rule and the previous one is subtle but super important. Before, we said that NEITHER Fernandez NOR Quinn could be before Turner, which meant that they BOTH had to be after Turner.

Now, though, the only thing that would be bad would be if BOTH Fernandez AND Quinn were before Turner. It would be totally fine if one or the other of them were before Turner. Just as long as they aren’t BOTH before him.

Let’s classify the possibilities into not ok and ok scenarios:

Not OK

- Fernandez and Quinn are both before Turner.

OK

- Fernandez is before Turner, but Quinn is after Turner.

- Quinn is before Turner, but Fernandez is after Turner.

- Fernandez and Quinn are both after Turner.

How to diagram

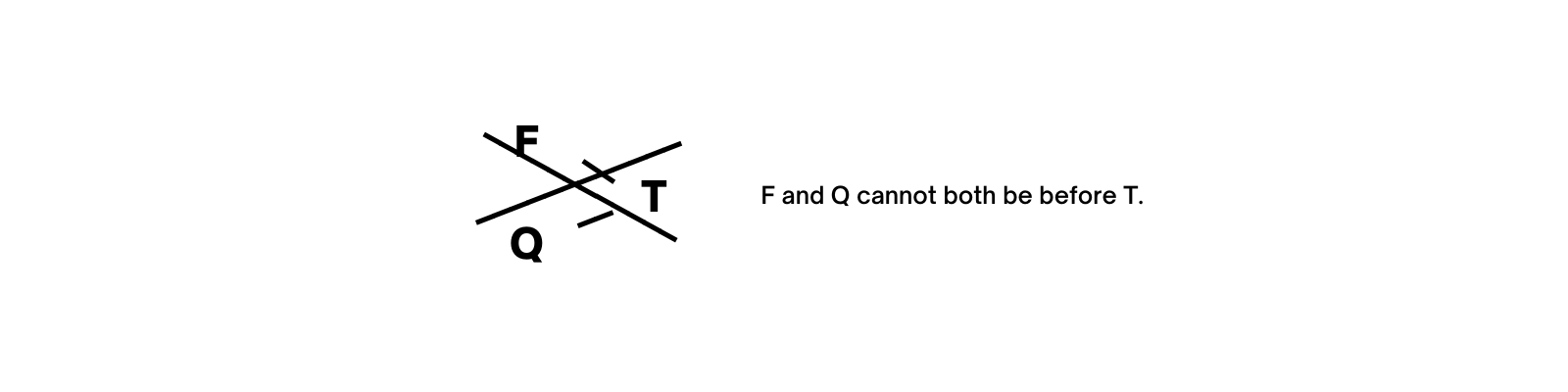

You’ve got a choice here. While there’s some degree of personal preference involved, one option is more efficient.

The most efficient way to do it is to diagram just the thing that’s not allowed, then cross it out to indicate that you can’t do that:

But you could also choose to diagram the things that ARE allowed. Use the word “OR” here to indicate that either of these three options could be true. It’s more complicated and might be harder to apply in the questions without making a mistake, but it’s still a valid way of writing the rule.

A little more about “or”

Remember that “or” on the LSAT implies “or both” unless it specifies otherwise. You get soup or salad OR BOTH. But here’s a weird exception. (Feel free to skip this part if it’s too weird.)

In this case, these three scenarios are mutually exclusive. They can’t happen at the same time. It’s like if the restaurant said “Pick Option A or Option B. Option A: you get soup but not salad. Option B: you get salad but not soup.” You can’t really choose both options here. Not because they said to pick only one option, but because picking option A is just incompatible with picking option B.

That’s why we would need to diagram all three of the OK scenarios.

And it’s why it’s probably a lot more efficient to just diagram the one not OK scenario.

Rule 2d: Either Fernandez or Quinn, but not both, must be seen before Turner.

Ok, here’s the LSAT adding a “but not both” to the “or.” The “not both” situation we have to watch out for here is putting both Fernandez and Quinn before Turner. That means that one of them will have to go after Turner.

We can again separate things into an OK and Not OK list.

OK

- Fernandez (but not Quinn) is before Turner. So Quinn is after Turner.

- Quinn (but not Fernandez) is after Turner. So Fernandez is after Turner.

Not OK

- Both Fernandez and Quinn are before Turner.

- Both Fernandez and Quinn are after Turner.

That last option on the Not OK list is there because that wouldn’t meet the requirement of one of either Fernandez or Quinn needing to be before Turner.

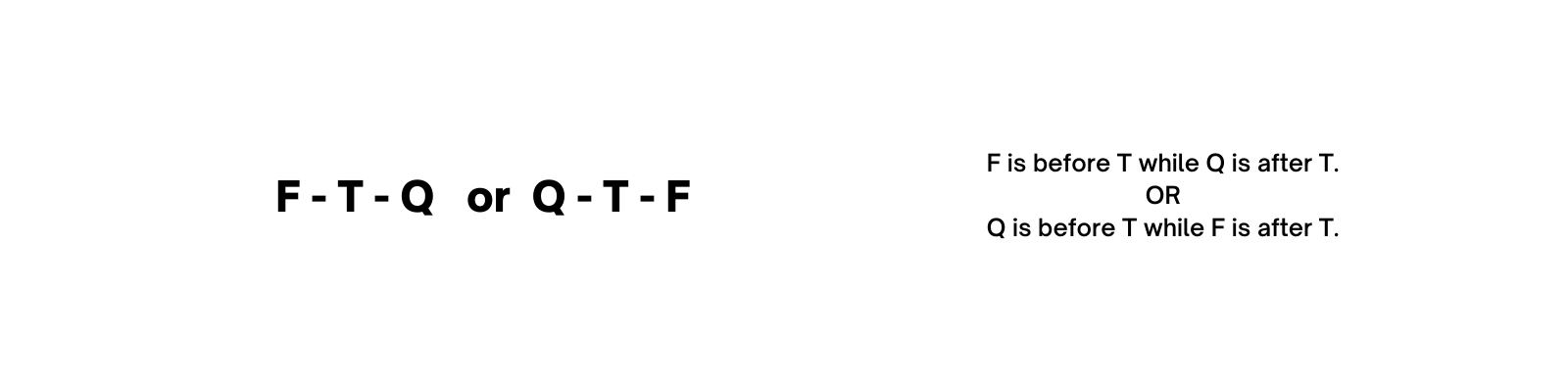

How to diagram

You’ve got choices again. You can diagram either the OK list or the NOT OK list. The lists are the same length, so it’s not like one option is going to be more efficient than the other. But generally, it’s easier on our brains to think about what’s allowed rather than what’s not allowed. So let’s diagram the OK list:

The plain English

What do these two diagrams have in common? In both of them, T is between the other two people. So we can essentially think of this rule as just “T is somewhere between F and Q.”

A word of caution

Make sure you don’t misinterpret your diagram to mean that T has to be right next to F and Q. The rule was just about before and after, not about “immediately before” or “immediately after”. If it had been, we would want to note that in our diagram, likely by removing the dashes and/or putting a box around the ones that have to go together.

Bonus question

How would you diagram this?

Turner must be seen immediately after Fernandez, but somewhere before Quinn.

Send me a message to check your answer.

What’s next

Move back to Part 1 if you missed it or move on to Part 3. Or read this post on making deductions in LG.

Part 1

- Turner is before Quinn or after Fernandez but not both.

- Neither Fernandez nor Quinn can be seen before Turner.

- Fernandez and Quinn cannot both be seen before Turner.

- Either Fernandez or Quinn, but not both, must be seen before Turner.

Part 3

- If Samuel is before Jacqueline, then Marco must be after Liu.

- Samuel is before Jacqueline only if Marco is after Liu.

- If Liu is before Marco, he must be immediately before Marco.

- Samuel must play immediately behind Jacqueline unless Liu plays before Marco.

LSAT Notes

If this post resonated with you, I’d love to stay in touch. About once a week, in the form of an email newsletter, I share useful strategies and insights I’ve picked up during my years teaching the LSAT. “LSAT Notes” you can use to study more effectively and raise your score.

Often these are inspired by breakthroughs my students had that week. Other times, they respond to questions students like you have. My goal is to provide motivation and encouragement along with knowledge about the test and advice about how to study.

Learn more about it here, or to subscribe, simply fill in the form below.